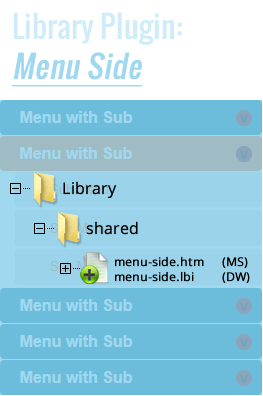

Left Sidebar Page

sidemenu, tabs and content

Site Menu

-

Fulfilled! 2025 Winter issue online!Dec. 23, 2025

-

New Commenting Capabilities!Sept. 10, 2025

-

New Sign-up Form for online readersMarch 21, 2021

-

New Web Site!Oct. 15, 2020

-

Mission StatementOct. 15, 2020

-

Reader BewareOct. 15, 2020

Our Mission:

Exploring and

proclaiming the good news of fulfilled

prophecy and life in Christ, equipping

and encouraging everyone in our journey

toward biblical truth, enabling each of

us to better discern and develop our

roles in the kingdom of God.

Past Fulfillment

The term "eschatology" refers to the

branch of theological study which deals with

"last things" or "end times." Therefore,

preterism, or "fulfilled eschatology" is the view that all

end-times promises and prophecies—including

the Second Coming of Christ, the

Resurrection of the Saints, and the Judgment

—have already been fulfilled.

Competing Views

One of several driving forces for the fulfilled interpretation is the many timing passages which, at face value, limit the expectations for these eschatological events to the first-century generation. On the other hand, the driving force for most Christians is their understanding of the nature of the fulfillment of these events. An oversimplification of this can be illustrated by the following passages:

The Revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave Him to show His servants—things which must shortly take place. He sent and signified it . . . to His servant John, who bore witness . . . to all things that he saw. Blessed is he who reads and those who hear the words of this prophecy, and keep those things which are written in it; for the time is near.

Behold, He is coming with clouds, and every eye will see Him, even they who pierced Him. And all the tribes of the earth will mourn because of Him. Even so, Amen. (Rev. 1:1-3, 7, NKJV. The New King James Version is used throughout unless other noted.)

Certainly to the original audience the time indicators (near) implied an imminent fulfillment of the prophecies under consideration, for one would not conclude from a face-value reading of the text that there were to be some two thousand years before the prophesied events would occur. Thus, preterism, for reasons shared below, looks for fulfillments within that prescribed timeframe.

Futurism, on the other hand, argues that Christ’s return was not seen by anyone in the first century, let alone "every eye." Therefore, futurism looks for the fulfillment of these events in our future.

It becomes immediately obvious that, for those who embrace preterism to believe Christ actually returned in the first century, something other than a literal understanding of "every eye will see him" must be employed. Conversely, though often not readily recognized, futurism must also employ something other than literal meanings to "shortly" and "near." R. C. Sproul spelled out this literal event versus literal time issue in reference to The Olivet Discourse as follows:

This problem of literal fulfillment leaves us with three basic solutions to interpreting The Olivet Discourse [i.e. Matthew Chapter 24]:

1. We can interpret the entire discourse literally. In this case we must conclude that some elements of Jesus’ prophecy failed to come to pass, as advocates of "consistent eschatology" maintain.

2. We can interpret the events surrounding the predicted parousia literally and interpret the time-frame references figuratively. This method is employed chiefly by those who do not restrict the phrase "this generation will not pass away" to the lifespan of Jesus’ contemporaries.

3. We can interpret the time-frame references literally and the events surrounding the parousia figuratively. In this view, all of Jesus’ prophecies in The Olivet Discourse were fulfilled during the period between the discourse itself and the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70.

The third option is followed by preterists. The strength of the preterist position is found precisely in this hermeneutical method. When faced with the option of interpreting the time-frame references literally or interpreting the description of the parousia literally, the preterist chooses the former. The preterist’s choice is governed by a larger hermeneutical principle, namely the principle of interpreting Scripture by Scripture (analogia fide). . . . there is much biblical precedent for interpreting figuratively references to astronomical upheavals in biblical prophecies of catastrophic events. On the other hand, the time-frame references are not clothed in such imagery, but expressed in straightforward, ordinary language. Following Luther’s view of seeking the “plain sense” of a Scripture passage, preterists insist on interpreting the time-frame references in their prima facie (“plain”) sense. (The Last Days According to Jesus, pp. 66-67)

Literal vs. Spiritual

When the topic of "literal" interpretation surfaces, statements like "we hold to a literal interpretation of the Bible" and "they spiritualize or allegorize everything" are often thrown around. Although not necessarily intended, any non-literal interpretation can often become "guilty by association" with liberals who do not accept the Bible as the literal Word of God. Such is not the case with preterism. The debate isn't whether preterism or futurism accepts the Bible as the literal Word of God; that’s a given in both cases. Rather, the debate is, "What portions or passages have something other than a strictly literal interpretation?" As demonstrated above, both sides must employ a non-literal view to either the time statements or the nature statements. Because most of us have been raised with a futurist paradigm, we easily accept non-literal interpretations of the timing statements—"shortly" cannot literally mean shortly, and "near" cannot literally mean near if we are still waiting for Christ’s return two thousand years after those words were written. Yet we still claim that we "interpret the Bible literally." Likewise, knowing that Scripture describes God as a spirit, we realize that, even though passages speak of the "arm of the Lord,” God does not have a literal arm as do you or I. Therefore, the debate is not over the literal interpretation of the Bible, but over how to interpret the various genres (historical, metaphor, parable, etc.) presented in the text.

Audience Relevance

In helping to determine which biblical elements we interpret in a non-literal fashion, an important consideration is the concept of "audience relevance." Audience relevance dictates that we must ascertain who wrote or spoke the words, why, when, and where they were written or spoken, and how the original audience would and/or were expected to have understood them. We have a tendency to read Scripture from a twenty-first century, western-culture mindset. Thus, we read Scripture the way we understand it, and assume that such is how the original audience would have understood it. In other words, we read ourselves and our culture into the text. In order to rightly divide the Word of Truth (2 Tim. 2:15), we must strive to understand how the original audience understood and/or were meant to understand it in their contemporary setting. For example, the English word "let" typically means "to allow." However, several centuries ago "let" meant just the opposite to English-speaking people: it meant "to hinder" (cf. 2 Thess 2:7 in the KJV). This usage has been retained in the game of tennis in which a serve that clips the top of the net is called a "let." Rather than allowing the tennis ball to pass, the net actually hindered it. So as diligent students of God’s Word, we must attempt to determine how the original audience would have understood the message given to them

Relationship of Old and New Testaments

Part and parcel with audience relevance is the relationship between the Old and New Testaments. Many Christians believe the Old Testament is the foundation upon which the New Testament is built and that, when there are perceived inconsistencies between the two, the Old Testament takes precedent. Thus, we must interpret the New Testament in light of the foundation laid in the Old Testament. However, many others (including those who embrace preterism) believe the New Testament actually interprets the Old Testament and that, when there are perceived inconsistencies between the two, the New Testament takes precedent. This is because the Old Testament contains things which were shrouded in mystery, types, and shadows. These mysteries were revealed to the New Testament apostles, and the types and shadows were fulfilled in Christ and the New Covenant:

. . . and to make all see what is the fellowship of the mystery, which from the beginning of the ages has been hidden in God who created all things through Jesus Christ . . . . (Eph. 3:9)

. . . the mystery which has been hidden from ages and from generations, but now has been revealed to His saints. (Col. 1:26)

Furthermore, in the specific arena of eschatology, Peter clearly stated that the Old Testament prophets did not always understand the substance and timing of their prophecies, whereas Jesus promised His apostles that when the Spirit came He would teach them the things to come:

Of this salvation the prophets have inquired and searched carefully, who prophesied of the grace that would come to you, searching what, or what manner of time, the Spirit of Christ who was in them was indicating when He testified beforehand the sufferings of Christ and the glories that would follow. To them it was revealed that, not to themselves, but to us they were ministering the things which now have been reported to you through those who have preached the gospel to you by the Holy Spirit sent from heaven— things which angels desire to look into. (1 Pet. 1:10-12)

When He, the Spirit of truth, has come, He will guide you into all truth; for He will not speak on His own authority, but whatever He hears He will speak; and He will tell you things to come. (John 16:13-14)

Thus, Old Testament prophecies that were hidden in ages past and not understood clearly were revealed to the first-century apostles and saints. Therefore, the New Testament must be used as a divine commentary on the Old Testament. This is not to imply that the New Testament supersedes the Old Testament, for Paul stated that he taught nothing but what was found in Moses and the prophets. Rather, the New Testament completes the foundation of Scripture upon which doctrine and theology must be built, for it is "...built on the foundation of the apostles and prophets, Jesus Christ—the chief cornerstone . . . ." (Eph. 2:20)

Timing Passages

In our example from the opening verses of Revelation, we focused on the time-related words “shortly” and “near.” When one examines the New Testament, they will find a multitude of similar statements. Here are just a few:

For the Son of Man will come in the glory of His Father with His angels, and then He will reward each according to his works. Assuredly I say to you, there are some standing here who shall not taste death till they see the Son of Man coming in His kingdom. (Matt 16:27-28)

Assuredly, I say to you, this generation will by no means pass away till all these things take place. (Matt 24:34)

You also be patient. Establish your hearts, for the coming of the Lord is at hand. (James 5:8)

But the end of all things is at hand; therefore be . . . watchful in your prayers. (1 Peter 4:7-8)

Little children, it is the last hour . . . . (1 John 2:18)

While there are over one hundred such “imminency” statements concerning Christ’s return, the Judgment, and/or the Resurrection, there is not one passage which so much as hints that any of these eschatological events were to be expected beyond the first-century generation. However, just the opposite is true of Old Testament predictions of Christ’s first coming and the Resurrection, which were stated as being far off:

I see Him, but not now; I behold Him, but not near . . . . (Num 24:17)

Go your way, Daniel, for the words are closed up and sealed till the time of the end. (Dan 12:9)

But you, go your way till the end; for you shall rest [die], and will arise to your inheritance at the end of the days. (Dan 12:13)

While Daniel’s words were sealed till the “time of the end,” John’s Revelation was not sealed: Do not seal the words of the prophecy of this book, for the time is at hand. (Rev. 22:10-11)

Likewise, Daniel was told he would die (rest) and be raised at the time of the end, while Paul wrote the Corinthians that they would not all die (sleep): I tell you a mystery: We shall not all sleep, but we shall all be changed . . . . (1 Cor. 15:51)

It is these timing passages—and numerous others—which cause those who embrace preterism to consider first-century fulfillments for the prophecies of the Second Coming of Christ, the Resurrection, and the Judgment.

Apocalyptic Language

As mentioned earlier, if we're to assume that Christ actually returned to His generation, we cannot take the phrase “every eye will see Him” in Revelation 1:7 in a strictly literal sense. Keep in mind, however, that if we believe Christ has not yet returned, there are over one hundred imminency passages (near, at hand, shortly, quickly, etc.) which we cannot interpret in a strictly literal sense.

Much of the imagery used to describe the events that accompany the Second Coming—the sun not shining, the moon turning to blood, the various plagues of Revelation—is the use of what is called “apocalyptic language.” This language is recognized by Bible scholars as the use of symbolic, metaphoric descriptions applied to common-place events orchestrated by God. For example, when God delivered David from the hand of Saul and his enemies, David described his deliverance in apocalyptic language:

Then the earth shook and trembled; The foundations of heaven quaked and were shaken, Because He was angry. Smoke went up from His nostrils, And devouring fire from His mouth; Coals were kindled by it. He bowed the heavens also, and came down With darkness under His feet. He rode upon a cherub, and flew; And He was seen upon the wings of the wind. He made darkness canopies around Him, Dark waters and thick clouds of the skies. From the brightness before Him Coals of fire were kindled. . . . Then the channels of the sea were seen, The foundations of the world were uncovered, At the rebuke of the Lord, At the blast of the breath of His nostrils. (2 Sam 22:8-13, 16)

Interestingly, in the historical narratives of David’s conflicts with Saul, we never read of astronomical or tectonic activity playing a role or of God being seen physically at any time, even though the text states He was seen upon the wings of the wind. Yet this is how David described his deliverance. This language is used to describe God’s direction of human affairs in the judgment or blessing of individuals and nations. To have the sun, moon, or stars not give their light is descriptive of judgment:

Behold, the day of the Lord comes, Cruel, with both wrath and fierce anger, To lay the land desolate; And He will destroy its sinners from it. For the stars of heaven and their constellations Will not give their light; The sun will be darkened in its going forth, And the moon will not cause its light to shine. (The Lord judging Babylon, Isa 13:9-10)

All the host of heaven shall be dissolved, And the heavens shall be rolled up like a scroll; All their host shall fall down As the leaf falls from the vine, And as fruit falling from a fig tree. (The Lord judging Edom, Isa 34:1)

The earth quakes before them, The heavens tremble; The sun and moon grow dark, And the stars diminish their brightness. (The Lord judging Israel, Joel 2:10)

Conversely, an increase in the brightness of the moon and the sun is representative of blessing:

For the people shall dwell in Zion at Jerusalem; You shall weep no more. He will be very gracious to you at the sound of your cry; When He hears it, He will answer you . . . . Moreover The light of the moon will be as the light of the sun, And the light of the sun will be sevenfold, As the light of seven days, In the day the Lord binds up the bruise of His people And heals the stroke of their wound. (Isa 30:19, 26)

Surely it would not be a blessing if the sun’s brightness were to literally increase sevenfold! Note that this same type of Old Testament imagery is used to describe Christ’s Second Coming:

Immediately after the tribulation of those days the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light; the stars will fall from heaven, and the powers of the heavens will be shaken. (Matt 24:29)

I looked when He opened the sixth seal, and behold, there was a great earthquake; and the sun became black as sackcloth of hair, and the moon became like blood. And the stars of heaven fell to the earth, as a fig tree drops its late figs when it is shaken by a mighty wind. Then the sky receded as a scroll when it is rolled up, and every mountain and island was moved out of its place. (Rev. 6:12-14)

Since the Old Testament apocalyptic passages were descriptions of God’s judgment upon nations, could not this same type of language in the New Testament also be associated with God’s judgment? Doesn't the Bible describe Jesus as coming to judge the nations in His Second Coming? Consider also the fact that Jesus prophesied Jerusalem’s destruction, and His disciples associated that event with His coming!

Then Jesus went out and departed from the temple, and His disciples came up to show Him the buildings of the temple. And Jesus said to them, “Do you not see all these things? Assuredly, I say to you, not one stone shall be left here upon another [judgment], that shall not be thrown down.” Now as He sat upon the Mount of Olives, the disciples came to Him privately, saying, “Tell us, when will these things be? And what will be the sign of Your coming, and of the end of the age?” (Matt 24:1, 3)

Moreover, Jesus stated that He only did what He saw the Father do and that the Father had committed all judgment to the Son. Should we not expect Jesus to judge the nations as the Father had judged them in the Old Testament?

Then Jesus answered and said to them, “Most assuredly, I say to you, the Son can do nothing of Himself, but what He sees the Father do; for whatever He does, the Son also does in like manner. . . . For the Father judges no one, but has committed all judgment to the Son.” (John 5:19, 22)

If we can accept that the apocalyptic language describing Christ’s Second Coming is not to be understood in a literal sense—just as it is not literal in the Old Testament, we can begin to see that the nature of Christ’s Second Coming is not necessarily what we may have traditionally believed it to be.

Cloud Comings

Closely associated with apocalyptic language is the concept of “cloud comings.” We are all familiar with the fact that Jesus’ Second Coming was stated to be with clouds:

Behold, He is coming with clouds . . . . (Rev 1:7)

Then we who are alive and remain shall be caught up together with them in the clouds to meet the Lord in the air. (1 Thess 4:17)

And the high priest answered and said to Him, “I put You under oath by the living God: Tell us if You are the Christ, the Son of God! ” Jesus said to him, “It is as you said. Nevertheless, I say to you, hereafter ['soon' per the Contemporary English Version] you will see the Son of Man sitting at the right hand of the Power, and coming on the clouds of heaven.” (Matt 26:63-64)

Recalling the principle of audience relevance discussed earlier, we must ascertain how the first-century readers would have understood this cloud-coming language. Furthermore, when we consider that the New Testament was written mainly by Jewish authors to a predominately Jewish audience, we realize that we must seek to understand how cloud-coming language was used and understood by the Jews.

Upon examining the Old Testament, which is the basis of Jewish culture, we find that the concept of God “coming on clouds” was part of their language. Cloud-coming language is often used to describe God coming in judgment of His enemies and/or deliverance of His people:

The burden against Egypt. Behold, the Lord rides on a swift cloud, And will come into Egypt; The idols of Egypt will totter at His presence, And the heart of Egypt will melt in its midst. (Isa 19:1)

For the day of the Lord is coming, For it is at hand: A day of darkness and gloominess, A day of clouds and thick darkness, Like the morning clouds spread over the mountains. (Joel 2:1-2)

The great day of the Lord is near; It is near and hastens quickly. The noise of the day of the Lord is bitter; There the mighty men shall cry out. That day is a day of wrath, A day of trouble and distress, A day of devastation and desolation, A day of darkness and gloominess, A day of clouds and thick darkness . . . . (Zeph 1:14-15)

Although there were literal judgments and/or deliverances occurring in these passages, they were described figuratively with cloud-coming language—God Himself was never seen on clouds or on the earth. Since this is the pattern established by God in the Old Testament, and since Jesus said that He would come in judgment as He had seen the Father come in judgment, and since He described His Second Coming with cloud-coming language, why should we expect to see Jesus physically and bodily in clouds at His coming? The Father was not seen when He came in judgment.

End of the World

It may be objected that, “While God’s Old Testament cloud comings were described in apocalyptic language, the end of the world was never predicted along with those judgments; on the other hand, Christ’s return is to occur at the end of the world. Therefore, there is a significant difference between the Old Testament descriptions of God coming on the clouds and Christ’s Second Coming on the clouds.”

The phrase “the end of the world” is due largely to a poor translation in the King James Version. Newer versions have corrected this phrase to read more accurately as “the end of the age.” Thus (just as the Bible never speaks of “the end of time”), it was not the end of the world that was expected to accompany Christ’s return, but the end of the age, i.e. the Old Covenant age. Note the difference between the King James and the New King James translations of Matthew 24:3:

. . . the disciples came unto him privately, saying, Tell us, when shall these things be? and what shall be the sign of thy coming, and of the end of the world? (Matt 24:3, KJV)

. . . the disciples came to Him privately, saying, “Tell us, when will these things be? And what will be the sign of Your coming, and of the end of the age?” (Matt 24:3, NKJV)

Just as the timing passages confine Christ’s Second Coming to the first-century generation, they place the end of the age squarely in that generation as well:

Now all these things happened to them as examples, and they were written for our [first-century audience] admonition, upon whom the ends of the ages have come. (1 Cor 10:11)

. . . but now, once at the end of the ages, He has appeared to put away sin by the sacrifice of Himself. (Heb 9:26-27)

The Old Covenant was drawing to a close in the first century, and when Jerusalem was destroyed by the Romans in AD 70 it ended forever. In AD 30 Christ had wept over the city and predicted its judgment in that generation. Forty years later—the span of a biblical generation—the city was destroyed. Just as God had used foreign armies to carry out His judgments in the Old Testament, so Christ used the Roman armies to come in judgment upon apostate Israel. Just as God’s Old Testament judgments were described in apocalyptic language and as comings in/on clouds, so Christ’s return was described in apocalyptic language and as coming in/on clouds. And just as God was never seen by the physical eye during His judgments, so Christ was not seen by the physical eye during His Second Coming.

The Kingdom

Those who embrace preterism believe the timing passages confine all eschatological fulfillments to the first century. They also believe Christ’s Second Coming (described in the same apocalyptic and cloud-coming language precedents of the Old Testament) was fulfilled in the same nature as God’s Old Testament comings.

“Where, then, is the kingdom?” one might ask. “Isn’t Christ supposed to establish an earthly kingdom upon His return?” Recall that Jesus told His disciples that the Holy Spirit would “teach them the things to come,” and that the New Testament expounds and explains much of what was shrouded in types and hidden in mysteries in the Old Testament. The New Testament never speaks of a future, physical kingdom ruled by Christ on Earth. This concept must be imported from Old Testament passages, which are then applied in a woodenly literalistic manner.

While the Jews and Samaritans debated where exactly one was to worship God, Jesus told the woman at the well that the hour had come when neither in Jerusalem nor in Samaria would true believers worship; rather, God was to be worshipped in spirit and in truth (John 4). Christ came to establish a spiritual kingdom (John 18:36) in which He rules and reigns in the hearts of His people, not to sit on a physical throne. The Jews who did not understand the typology and mystery of the Old Testament were looking for a literal king to reign over a physical kingdom. Thus, they tried to take Jesus by force and make Him king, but Christ eluded them (John 6:15). If Jesus came preaching the kingdom, and the kingdom He had in mind had been physical in nature, why did He reject the efforts of the Jews to crown Him king? Like the Jews of Jesus' time, much of Christianity today is directly applying Old Testament passages to Christ’s kingdom without having rightly interpreted them via the insight of the New Testament.

Conclusion

When all of this is taken into consideration, the logic of preterism begins to come into focus. The promised return of Christ was taught and expected within the time frame of the first-century generation. It was foretold in the same type of language used in the Old Testament to foretell national judgments. While this language spoke of astronomical signs and God coming on clouds, there is no evidence of any astronomical phenomena or of God ever being seen with the physical eye. The Second Coming of Christ is described in this same language, and we see in the destruction of Jerusalem in AD 70 a fulfillment similar to the judgments rendered upon the Old Testament nations. Just as promised, this took place forty years after Jesus foretold it—within that generation.

For those who feel that preterism is “redefining” the nature of Christ’s Second Coming, keep in mind that if someone believes the Lord's return is still future, they are redefining all of the timing passages which describe the first-century nearness of His return. Furthermore, preterists would claim that they are not redefining the scriptural depiction of Christ’s Second Coming, but rather they are redefining the Church’s traditional interpretation of the Second Coming.

While, as demonstrated, there’s ample biblical precedent for apocalyptic and cloud-coming language being metaphorical in nature, there’s no biblical precedent for redefining time statements. We would remind the reader of the opening example from Revelation:

The Revelation of Jesus Christ, which God gave Him to show His servants—things which must shortly take place. And He sent and signified it by His angel to His servant John, who bore witness to the word of God, and to the testimony of Jesus Christ, to all things that he saw. Blessed is he who reads and those who hear the words of this prophecy, and keep those things which are written in it; for the time is near. (Rev. 1:1-3)

Behold, He is coming with clouds, and every eye will see Him, even they who pierced Him. And all the tribes of the earth will mourn because of Him. Even so, Amen. (Rev. 1:7)

The times statements (shortly take place and time is near) and the “every eye will see Him” statement cannot both be taken in a strictly literal sense; therefore, one or both must have been meant to be taken non-literally. Preterism holds that biblical precedent establishes the metaphorical use of apocalyptic and cloud-coming language, while time statements are to be understood by their natural meanings. Obviously, this is but a brief introduction, so you are encouraged to study these topics, examining the Scriptures to see if these things are true (Acts 17:11).

Fulfilled

Fulfilled